BSc Thesis IV

Domain-Dependent Policy Learning using Neural Networks for Classical Planning (4/4)

This will be the forth and final post of my undergraduate dissertation series. It will cover the detailed evaluation of Action Schema Networks conducted for classical automated planning, propose future work that might deal with identified weaknesses before concluding the project as a whole.

Evaluation

As mentioned in the second post of this series, Sam Toyer already conducted an empirical evaluation of ASNets [1], but primarily focused on probabilistic planning tasks. While he also considered classical planning, these experiments were only performed for the Gripper domain which is solved fairly easily by most considered baseline planners. Therefore, we decided to extensively evaluate the method considering multiple domains of varying complexity and comparing ASNets performance to successful satisficing and optimal planners.

Evaluation Objectives

The goal of this evaluation is to answer the following questions with respect to the suitability of ASNets to solve classical planning tasks:

- Are ASNets able to learn effective (maybe even optimal) policies? We use satisficing and optimal teacher search configuration during training. We expect that ASNet policies will be constrained in their quality by the applied teacher search. However, it is essential to observe to what extent the policies reach and potentially even exceed the teacher’s effectiveness.

- Which properties have domains in common, on which ASNets are able to perform well? Such findings about apparent limitations and strengths of the method can enable further progress to improve learning techniques for automated planning applications.

- For which period of time need ASNets to be trained until they perform reasonably well? It is to be expected that training time significantly depends on the used configuration and planning domain.

Evaluation Setup

Hardware

The evaluation including execution and training of all baseline planners and ASNet configurations was run on a x86064 server using a single core of a Intel Xeon E5-2650 v4 CPU clocked at 2.2GHz and 96GiB of RAM.

Domains and Problems

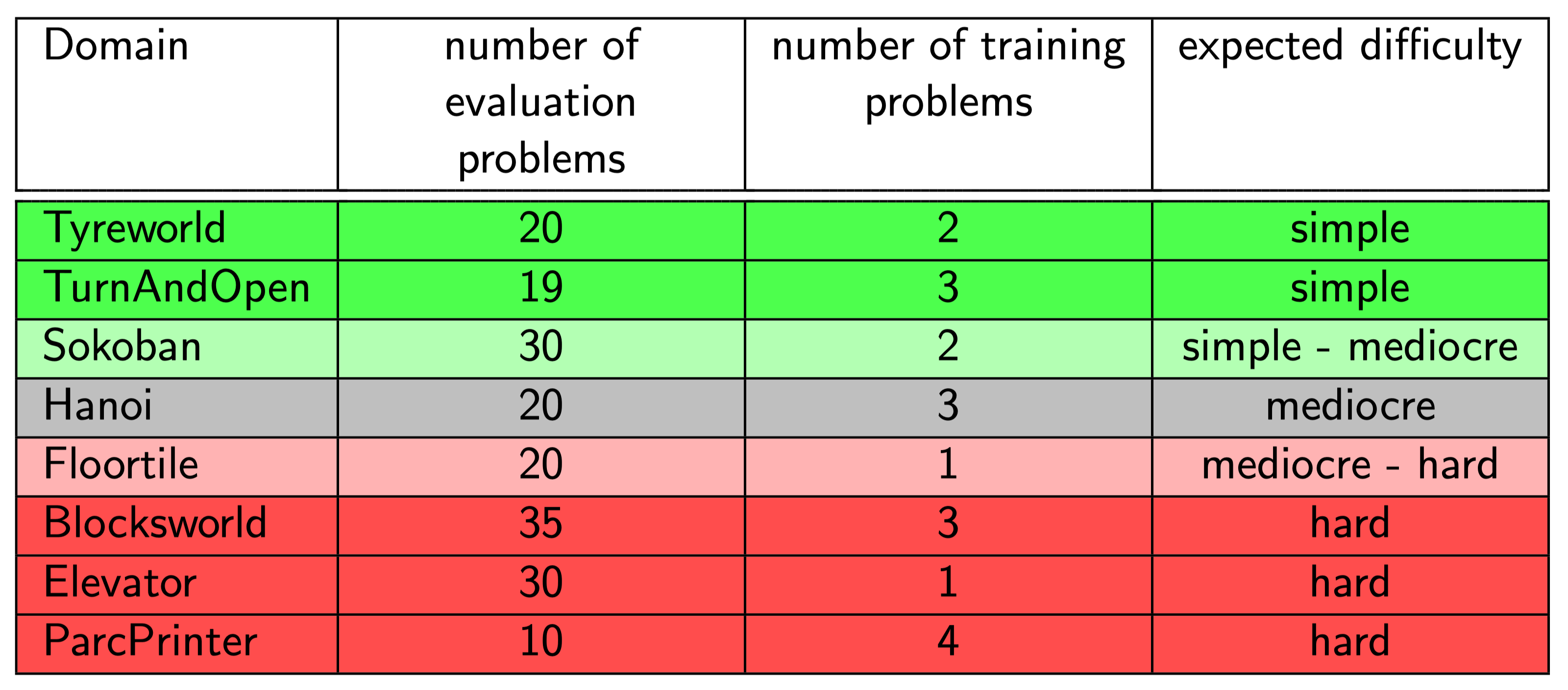

We use eight domains of different complexity and characteristics to reliably evaluate ASNets. These are mostly taken from previous iterations of the International Planning Competition (IPC) and the FF-Domain collection of Prof. Dr. Hoffmann. All domains with the number of problem instances used for ASNet training and evaluation as well as the expected difficulty can be found in the table below.

For details on the domains and used problem instances, see Section 7.2.1 of the thesis.

Baseline Planners

As baseline planners, three primary heuristic search approaches were used which dominate classical automated planning. All baselines were implemented in the Fast-Downward planning system [2] and their search time for each problem will be limited at 30 minutes.

$A^*$ with $h^{LM-cut}$ or $h^{add}$: $A^*$ is one of the most popular heuristic search algorithms. It maintains a prioritised open list of states ordered by their f-value which is the sum of the cost $g(s)$ to reach the state as well as its heuristic value $h(s)$. In each iteration, the state with the lowest f-value is expanded and its children added to the list if it is no goal state already. This process starts at the initial state and is continued until a goal is reached or the task is found unsolvable when the open list becomes empty. Whenever applied with admissible heuristics, $A^*$ is guaranteed to find optimal plans that minimise the cost [3]. Despite being fairly expensive, this is why the algorithm is still widely used in optimal planning. As heuristic functions, we use the admissible LM-cut heuristic [3] as well as the inadmissible, additive heuristic $h^{add}$ [5].

Greedy best-first search with $h^{FF}$: Greedy best-first search (GBFS) is the pendant of $ A^* $ for satisficing planning proposed by Russell and Norvig [6]. The algorithms share the same procedure, but GBFS uses the heuristic values of states alone as the open list priorities instead of f-values. For most domains, GBFS is considerably faster in finding a plan than $A^*$, but it provides no optimality guarantees. The search is used with the relaxed plan heuristic $H^{FF}$ [7] using a dual-queue with preferred operators. This setup has proven to be fairly effective for application in satisficing planning.

LAMA-2011: The LAMA-2011 planning system [8] was one of the winners at the 2011 IPC and combines multiple approaches from previous searches. It starts with GBFS runs combining the relaxed plan heuristic with landmark heuristics [9] to quickly find a plan. Afterwards, it iteratively aims to improve and find better plans using (weighted) $A^*$ and pruning techniques.

ASNet configurations

All evaluation will be executed using the same ASNet configuration. A hidden representation size $d_h = 16$ and two layers will be used. In all intermediate nodes, the ELU activation function [10] is applied and to minimise overfitting, we apply the L2-regularisation with $\lambda = 0.001$ as well as dropout [11] with a probability of $p = 0.25$.

Training is executed for $T_{max-epochs} = 10$ with $T_{prob-epochs} = 3$ each. Training is limited at two hours. It is worth noting, that training samples for each problem are accumulated in each epoch to maximise sample efficiency. On each problem, $T_{train-epochs} = 100$ are executed using the Adam optimizer [12] with a learning rate of $\alpha = 0.001$. As the teacher searches during training, we use the optimal $A^*$ with $h^{LM-cut}$, as well as $A^*$ with $h^{add}$ and GBFS with $h^{FF}$.

Evaluation Results

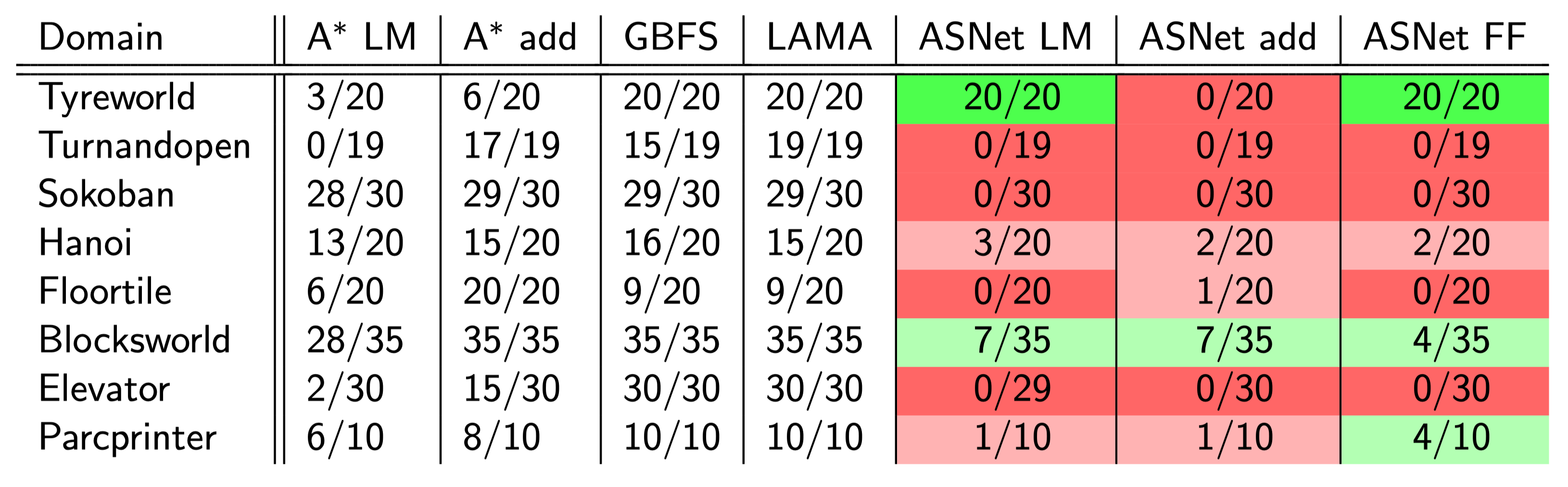

A brief overview over the evaluation results clearly indicates, that ASNets were unable to learn effective policies for most domains and tasks with Tyreworld being the notable exception.

For the Floortile and TurnAndOpen domain, it turns out that the teacher searches simply take too long. Hence, the sampling during training did not terminate in time and hardly any training could be completed. It is unsurprising that ASNets were unable to solve these tasks given these issues. However, it could be observed, that learned plans for the Floortile domain successfully avoided potential dead-ends. These were previously identified as the major challenge of the domain, such that it was surprising to see this success, despite brief training.

The domains Floortile, Sokoban and TurnAndOpen all require some form of movement through an environment. Unfortunately, these movement actions can often be chosen interchangeably due to symmetries in the environment. This led to related actions having almost equal probabilities to be chosen. This frequently caused ASNets to choose inverting actions to return into a previously encountered state. Given the simple policy search applied using the ASNet policy, this immediately resulted in a failure of the planning procedure to avoid circular search.

Training data for the domains Blocksworld, Hanoi and ParcPrinter looked very promising. Training was consistently terminated even before an hour for Hanoi and Blocksworld and reached stable success rates (solving the problems currently trained on) of above 70%. However, such performance did hardly generalise beyond the set of problem instances used during training. For Blocksworld and Hanoi, we assume that problem instances are too diverse requiring very different solutions despite the common domain. On the ParcPrinter domain however, it could be observed that large parts of the required scheduling was learned perfectly. Only one of the last few tasks was consistently failed which involves printing the correct images on selective sheets. We are unsure about why ASNets were capable of learning the previous scheduling tasks flawlessly, but failed to learn this part of the process.

The only domain on which ASNets generalised and performed well is Tyreworld. We previously anticipated that it would be one of the easiest domains due to its repetitious patterns which can be learned and simply repeated for each tyre. Additionally, it seems to be essential that each subproblem of replacing a tyre is independent and hence these can be executed in any order. Therefore, any indecisiveness of ASNets with respect to the order of these actions did not harm the performance on the problems.

Scalability Concerns

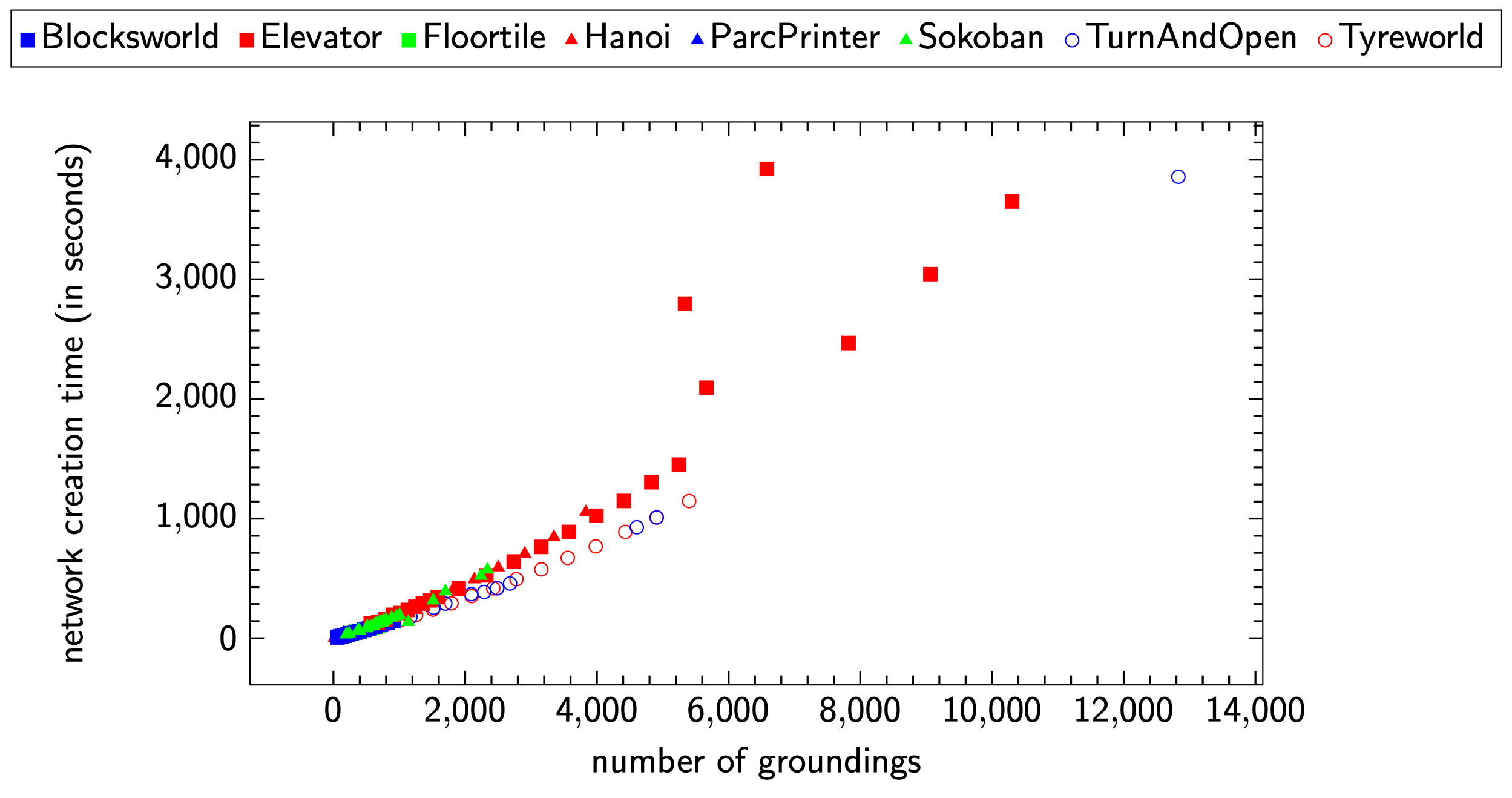

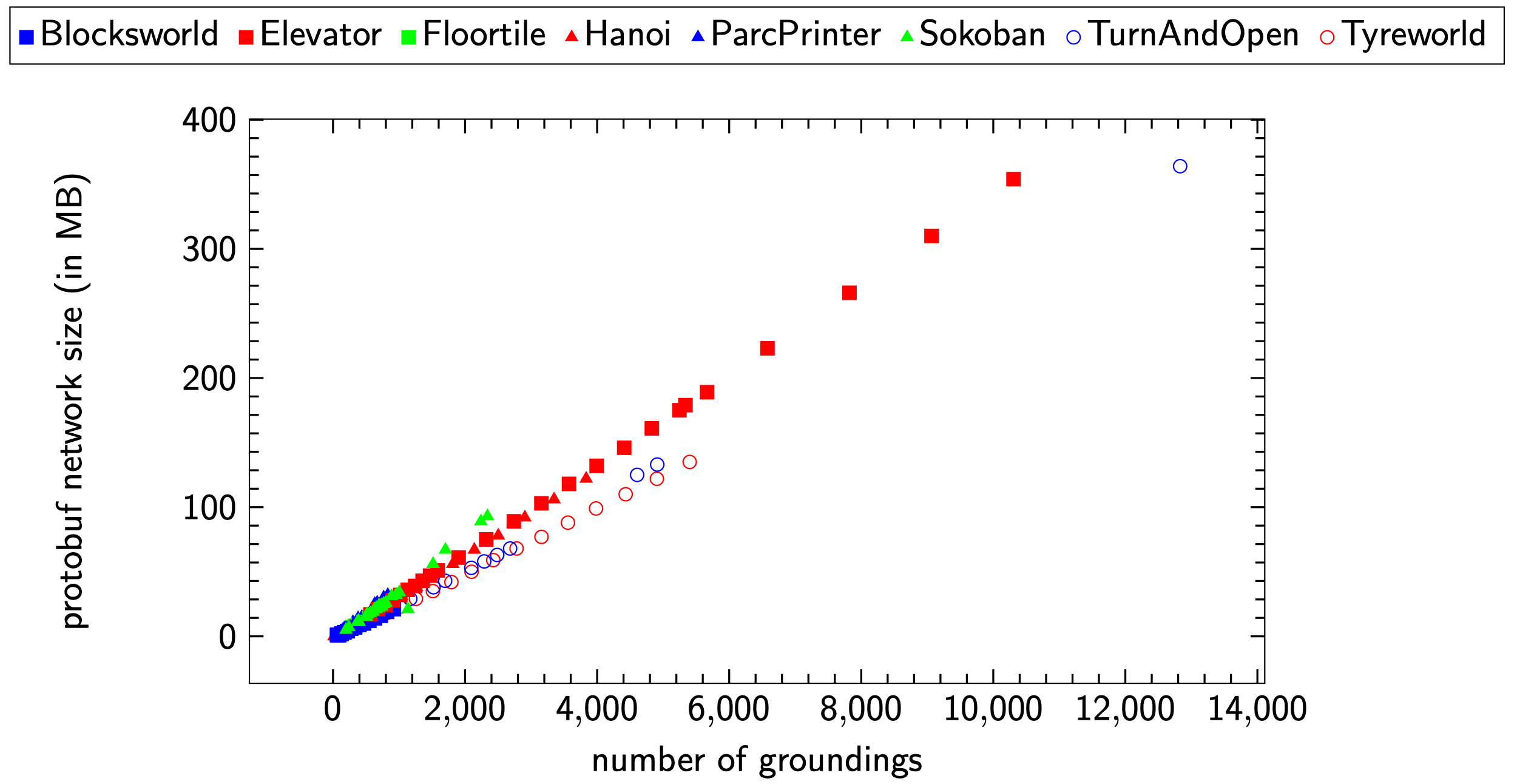

However, even on the Tyreworld domain, a considerable weakness of ASNets could be identified. The networks contain one module for each grounding in every layer which causes the networks to blow up in size fairly quickly. Below, you can see figures showing the increase in size and creation time for networks for the evaluated planning tasks.

While most domains are not problematic as they involve at most 1,000 - 2,000 groundings, few domains like TurnAndOpen or Elevator will involve much more groundings. Creation time and network size linearly increase with the number of groundings, and it becomes hard to justify training if the generation of such a model takes 30 minutes and more.

Unstable Training

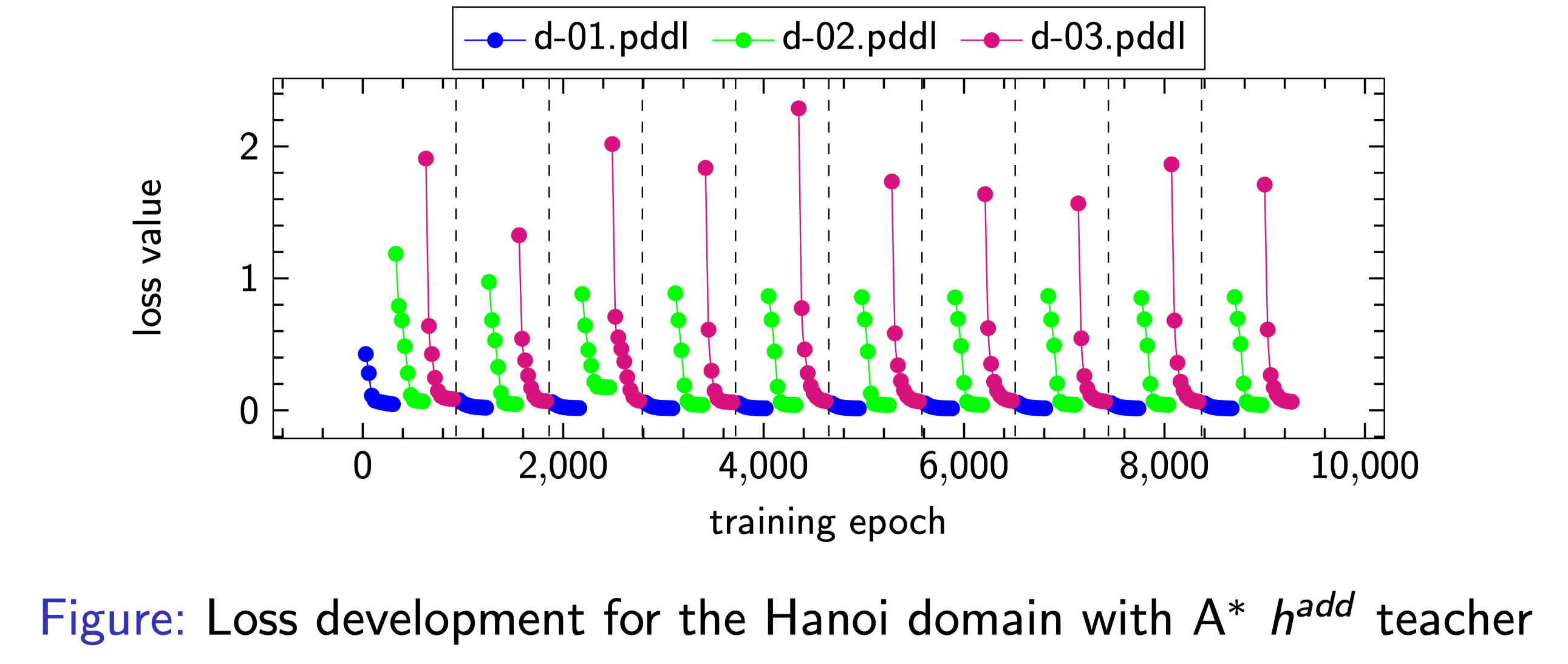

Besides these considerable scalability issues, we also observed that training was highly unstable. It appears that training on each problem quickly converges to good performance and low loss values. However, any such convergence seems to indicate overfitting and reverts any previous progress on other problem files. This leads to no consistent improvement during training.

This figure shows such loss development during training on the Hanoi domain. Similar plots could be observed for the majority of domains.

Future Work

This project serves as a starting point to get insight into the potential application of deep learning methods for policy learning in classical automated planning tasks. There are many logical extensions and related approaches worth exploring for future research in this field.

Additional Input Features

One straight-forward extension, which should be implemented for classical planning, are additional heuristic input features as they were already proposed and evaluated by Sam Toyer [1, 13]. While our work considered such inputs and already provides the framework for such additions, they were not implemented yet due to time constraints. Previous work considered binary values representing landmarks computed by the LM-cut heuristic. These features were found to assist ASNets in overcoming limitations in their receptive field. We propose to consider non-binary values as well. While simplified inputs can assist learning, neural networks are generally able to learn complex relations and might extract more information out of non-binary values.

Besides additional heuristic input features, one could also provide action costs in the input. Currently, the network can not directly reason about action costs which are only indirectly recognized due to the teacher search values in samples. Providing cation costs as direct input might speed up learning and lead to less dependency with the teacher search for good network policies.

Sampling

During our sampling procedure, we collect data from states which are largely extracted from goal trajectories of the applied teacher search. Such information is useful to learn a reasonable policy, but also contains a strong bias as sampled states are heavily correlated to each other. This can lead to a bias of ASNet policies to simply imitate the teacher search and limits the ability to generalise to problems outside of the training set. We can imagine that this was one of the reasons why stable training was not achieved.

One approach to reduce the redundancy and bias of the sampling set is to reduce the number of sampled runs for goal trajectories of the teacher search. These trajectories often share large parts of their states and quickly dominate the sampling data. One could e.g. limit the teacher search sampling to only a single trajectory starting in the initial state. However, it would have to be analysed whether this significantly smaller sampling set is still sufficient to allow training progress.

Another approach to avoid such a bias entirely would be to use a uniform sampling strategy, i.e. collecting uncorrelated data randomly. This means, no teacher search to collect connected trajectories could be used due to their dependency. Sampling truly random states without an underlying bias from a planning problem state space is challenging, but could improve the quality of the sampling data and therefore the learning considerably.

Improved Policy Search

Another logical extension of our work would be the implementation of sophisticated search engines for policies. The current search simply follows the most probable action, which accurately represents the policy, but probably limits the effectiveness. Backtracking could be added to our existing approach using an open list of already encountered states. This would allow the search to continue whenever duplicate or dead-end states are reached without failing the entire planning procedure. This could already elevate performance in tasks involving interchangeable paths or dead-ends.

Second, one could aim to combine the ASNet policies with well-established heuristic search. The policy probabilities for actions could e.g. be used to decide in tiebreaking situations between multiple paths or one could combine the policies action probabilities and heuristic values to compute a common priority measure.

Furthermore, we identified symmetries in the state space to be a considerable challenge to ASNets. Pruning techniques capable of identifying and removing such paths could be used to prune these states and assist the network policy’s indecisiveness in these situations. Such pruning methods are well-researched in the planning community [14, 15].

Conclusion

The objective of this project was to evaluate the suitability of domain-dependent policy learning using Action Schema Networks for classical automated planning. We integrated this deep learning architecture in the Fast-Downward planning system. In doing so, we extended the PDDL translation to compute relations between abstract action schemas, predicates as well as their groundings, added a policy representation to the framework with a simple search and implemented the neural network architecture using Keras. The training procedure largely follows previous work of Sam Toyer, but extends the teacher policy to support arbitrary search configurations implemented in the Fast-Downward system. This leads to large flexibility given the various, already implemented planning strategies due to the system’s popularity.

Our extensive empirical evaluation aimed to primarily answer whether ASNets are suited to solve classical planning tasks. Although the network generalised poorly on most domains, significant learning could be found for most tasks. Hence, we would not consider ASNets strictly unsuitable, but rather found shortcomings in the approach taken primarily regarding its training and the sampling process. We provide analysis of the training process for each domain to identify encountered problems and based on our findings propose further research which might alleviate or even solve the identified challenges.

However, the final assessment regarding the suitability of Action Schema Networks for classical planning will depend on the results of further research building upon our work.

For more details on this project, see my undergraduate thesis or feel free to reach out to me (contact information can be found below).

References

- Toyer, S. (2017). Generalised Policies for Probabilistic Planning with Deep Learning (Research and Development, Honours thesis). Research School of Computer Science, Australian National University.

- Helmert, M. (2006). The Fast Downward Planning System. J. Artif. Int. Res., 26(1), 191–246. Retrieved from http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1622559.1622565

- Hart, P. E., Nilsson, N. J., & Raphael, B. (1972). A Formal Basis for the Heuristic Determination of Minimum Cost Paths. SIGART Bull., (37), 28–29. https://doi.org/10.1145/1056777.1056779

- Helmert, M., & Domshlak, C. (2009). Landmarks, Critical Paths and Abstractions: What’s the Difference Anyway? (pp. 162–169).

- Bonet, B., & Geffner, H. (2001). Planning as Heuristic Search. Ai, 129(1–2), 5–33.

- Russell, S., & Norvig, P. (1995). Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. prenticeort: prentice.

- Hoffmann, J., & Nebel, B. (2001). The FF Planning System: Fast Plan Generation Through Heuristic Search. Jair, 14, 253–302.

- Richter, S., Westphal, M., & Helmert, M. (2011). LAMA 2008 and 2011 (planner abstract). In IPC 2011 planner abstracts (pp. 50–54).

- Richter, S., & Westphal, M. (2010). The LAMA Planner: Guiding Cost-Based Anytime Planning with Landmarks. Jair, 39, 127–177.

- Clevert, D.-A., Unterthiner, T., & Hochreiter, S. (2015). Fast and Accurate Deep Network Learning by Exponential Linear Units (ELUs). CoRR, abs/1511.07289. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1511.07289

- Srivastava, N., Hinton, G., Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I., & Salakhutdinov, R. (2014). Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 15, 1929–1958. Retrieved from http://jmlr.org/papers/v15/srivastava14a.html

- Kingma, D., & Ba, J. (2014). Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Toyer, S., Trevizan, F. W., Thiébaux, S., & Xie, L. (2017). Action Schema Networks: Generalised Policies with Deep Learning. CoRR, abs/1709.04271. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1709.04271

- Fox, M., & Long, D. The Detection and Exploitation of Symmetry in Planning Problems (pp. 956–961).

- Domshlak, C., Katz, M., & Shleyfman, A. (2015). Symmetry Breaking in Deterministic Planning as Forward Search: Orbit Space Search Algorithm.